Progressive Party (United States, 1912) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Progressive Party was a

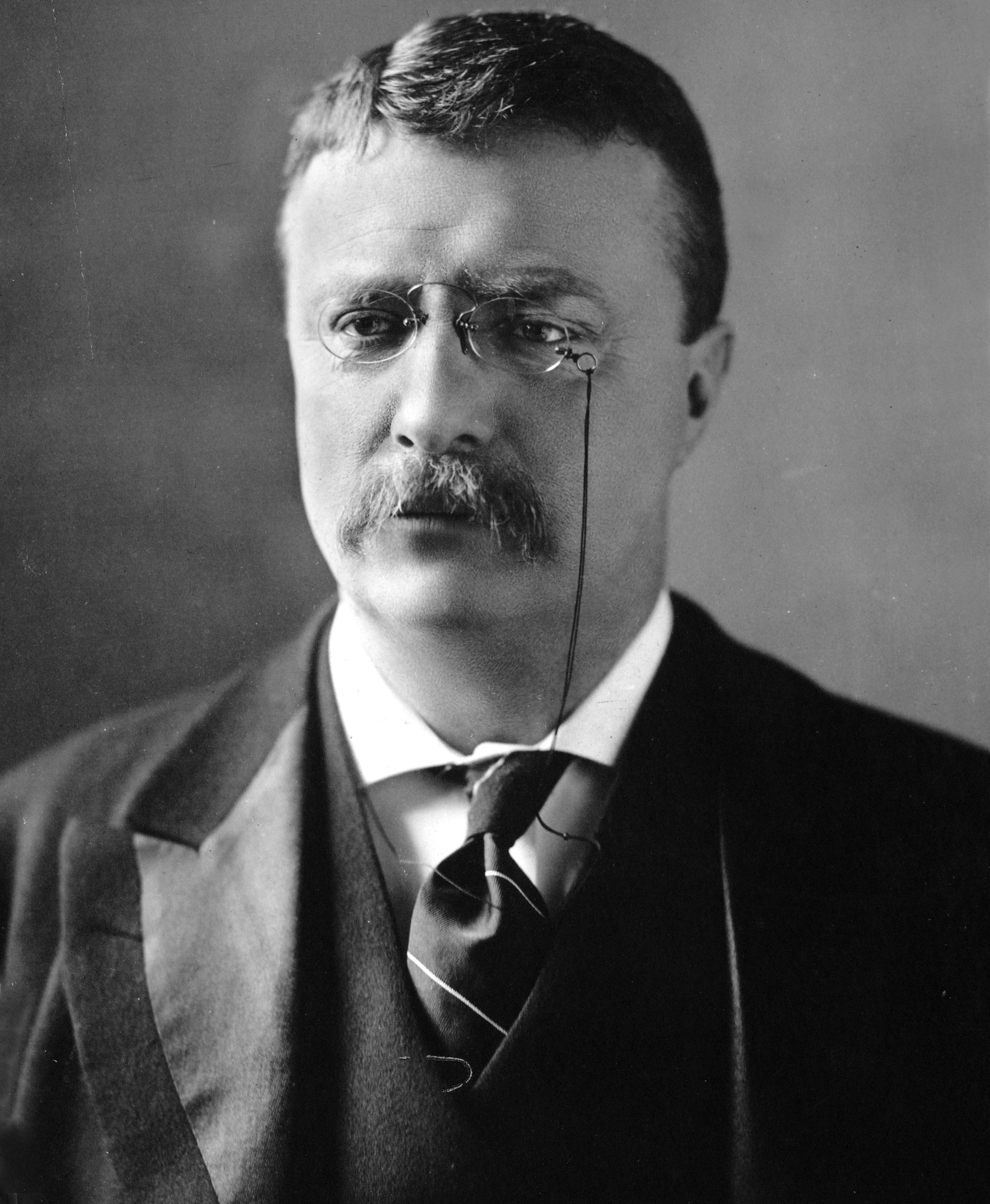

The Progressive Party was a  As a member of the Republican Party, Roosevelt had served as president from 1901 to 1909, becoming increasingly progressive in the later years of his presidency. In the 1908 presidential election, Roosevelt helped ensure that he would be succeeded by

As a member of the Republican Party, Roosevelt had served as president from 1901 to 1909, becoming increasingly progressive in the later years of his presidency. In the 1908 presidential election, Roosevelt helped ensure that he would be succeeded by

Roosevelt had selected Taft, his

Roosevelt had selected Taft, his

The leadership of the new party at the level just below Roosevelt included

The leadership of the new party at the level just below Roosevelt included

The platform's main theme was reversing the domination of politics by business interests, which allegedly controlled the Republican and Democratic parties, alike. The platform asserted:

To that end, the platform called for:

* Strict limits and disclosure requirements on political

The platform's main theme was reversing the domination of politics by business interests, which allegedly controlled the Republican and Democratic parties, alike. The platform asserted:

To that end, the platform called for:

* Strict limits and disclosure requirements on political

Roosevelt ran a vigorous campaign, but the campaign was short of money as the business interests which had supported Roosevelt in 1904 either backed the other candidates or stayed neutral. Roosevelt was also handicapped because he had already served nearly two full terms as president and thus was challenging the unwritten "no third term" rule.

In the end, Roosevelt fell far short of winning. He drew 4.1 million votes—27%, well behind Wilson's 42%, but ahead of Taft's 23% (6% went to

Roosevelt ran a vigorous campaign, but the campaign was short of money as the business interests which had supported Roosevelt in 1904 either backed the other candidates or stayed neutral. Roosevelt was also handicapped because he had already served nearly two full terms as president and thus was challenging the unwritten "no third term" rule.

In the end, Roosevelt fell far short of winning. He drew 4.1 million votes—27%, well behind Wilson's 42%, but ahead of Taft's 23% (6% went to  The Republican split was essential to allow Wilson to win the presidency. In addition to Roosevelt's presidential campaign, hundreds of other candidates sought office as Progressives in 1912.

Twenty-one ran for governor. Over 200 ran for

The Republican split was essential to allow Wilson to win the presidency. In addition to Roosevelt's presidential campaign, hundreds of other candidates sought office as Progressives in 1912.

Twenty-one ran for governor. Over 200 ran for

online

* Flehinger, Brett. ''The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: A Brief History with Documents'' (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2003). * Gable, John A. ''The Bullmoose Years: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party''. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1978. * Garraty, John A. ''Right Hand Man: The Life of George W. Perkins'', (1960

online

* Goodwin, Doris Kearns. ''The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism'' (2013) * Gould, Lewis L. ''Four hats in the ring: The 1912 election and the birth of modern American politics'' (University Press of Kansas, 2008). * Jensen, Richard. "Theodore Roosevelt" in ''Encyclopedia of Third Parties'' (ME Sharpe, 2000). pp. 702–707. * Karlin, Jules A. ''Joseph M. Dixon of Montana'' (U of Montana Publications in History, 1974) 1:130-190. * Kraig, Robert Alexander. "The 1912 Election and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State". ''Rhetoric and Public Affairs'' (2000): 363–395. . * Lincoln, A. “Theodore Roosevelt, Hiram Johnson, and the Vice-Presidential Nomination of 1912.” ''Pacific Historical Review'' 29#3 (1959), pp. 267–83

online

* Milkis, Sidney M., and Daniel J. Tichenor. "Direct Democracy' and Social Justice: The Progressive Party Campaign of 1912". ''Studies in American Political Development'' 8#2 (1994): 282–340. * Milkis, Sidney M. ''Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party, and the Transformation of American Democracy''. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009. * Mowry, George E. ''The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America''. New York: Harper and Row, 1962, national survey; it is not biographical on Roosevel

online

* Mowry, George E. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement''. (1946) focus on 1912

online

* Ness, Immanuel, and James Ciment, eds. ''The Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America'' (3 vol. 2000). * Selmi, Patrick. "Jane Addams and the Progressive Party Campaign for President in 1912". ''Journal of Progressive Human Services'' 22.2 (2011): 160–190.

online

* Huthmacher, J. Joseph. "Urban Liberalism and the Age of Reform" ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 49 (1962): 231–241, ; emphasized urban, ethnic, working class support for reform * Link, William A. ''The Paradox of Southern Progressivism, 1880–1930'' (1992). * Maxwell, Robert S. ''La Follette and the Rise of the Progressives in Wisconsin''. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1956. * Mowry, George E. ''The California Progressives'' (U of California Press, 1951)

online

* Olin, Spencer C. ''California's Prodigal Sons'' (Univ of California Press, 1968

online

* Pegram, Thomas R. ''Partisans and Progressives: Private Interest and Public Policy in Illinois, 1870-1922'' (U of Illinois Press, 1992)

online

* Recchiuti, John Louis. ''Civic Engagement: Social Science and Progressive-Era Reform in New York City'' (2007). * Warner, Hoyt Landon. ''Progressivism in Ohio 1897-1917'' (Ohio State UP, 1964) * Wesser, Robert F. ''Charles Evans Hughes: politics and reform in New York, 1905–1910'' (1967). * Wright, James. ''The Progressive Yankees: Republican Reformers in New Hampshire, 1906-1916'' (1987).

online

* DeWitt, Benjamin P. ''The Progressive Movement: A Non-Partisan, Comprehensive Discussion of Current Tendencies in American Politics'' (1915)

online

* Pinchot, Amos. ''What's the Matter with America: The Meaning of the Progressive Movement and the Rise of the New Party''. (1912

online

* Pinchot, Amos. ''History of the Progressive Party, 1912–1916''. Introduction by Helene Maxwell Hooker. (New York University Press, 1958

online

* Roosevelt, Theodore. ''Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt'' Ed. Lewis L. Gould. (UP of Kansas, 2008).

TeddyRoosevelt.com: Bull Moose Information

Theodore Roosevelt Speech Edison Recordings Campaign - 1912

''1912 Progressive Party platform''

at

The Progressive Party was a

The Progressive Party was a third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a V ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

formed in 1912 by former president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

after he lost the presidential nomination of the Republican Party to his former protégé rival, incumbent president William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

. The new party was known for taking advanced positions on progressive reforms and attracting leading national reformers. The party was also ideologically deeply connected with America's indigenous radical-liberal tradition.

After the party's defeat in the 1912 presidential election, it went into rapid decline in elections until 1918, disappearing by 1920. The Progressive Party was popularly nicknamed the "Bull Moose Party" when Roosevelt boasted that he felt "strong as a bull moose" after losing the Republican nomination in June 1912 at the Chicago convention.

As a member of the Republican Party, Roosevelt had served as president from 1901 to 1909, becoming increasingly progressive in the later years of his presidency. In the 1908 presidential election, Roosevelt helped ensure that he would be succeeded by

As a member of the Republican Party, Roosevelt had served as president from 1901 to 1909, becoming increasingly progressive in the later years of his presidency. In the 1908 presidential election, Roosevelt helped ensure that he would be succeeded by Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Taft. Although Taft entered office determined to advance Roosevelt's Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

domestic agenda, he stumbled badly during the Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act

The Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act of 1909 (ch. 6, 36 Stat. 11), named for Representative Sereno E. Payne (R– NY) and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich (R– RI), began in the United States House of Representatives as a bill raising certain tariffs on goo ...

debate and the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy

The Pinchot–Ballinger controversy, also known as the "Ballinger Affair", was a dispute between U.S. Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger that contributed to the split of the Republican P ...

. The political fallout of these events divided the Republican Party and alienated Roosevelt from his former friend. Progressive Republican leader Robert M. La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

had already announced a challenge to Taft for the 1912 Republican nomination, but many of his supporters shifted to Roosevelt after the former president decided to seek a third presidential term, which was permissible under the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

prior to the ratification of the Twenty-second Amendment. At the 1912 Republican National Convention, Taft narrowly defeated Roosevelt for the party's presidential nomination. After the convention, Roosevelt, Frank Munsey, George Walbridge Perkins

George Walbridge Perkins I (January 31, 1862 – June 18, 1920) was an American politician and businessman. He was a leader of the Progressive Movement, especially Theodore Roosevelt's presidential candidacy for the Progressive Party in 191 ...

and other progressive Republicans established the Progressive Party and nominated a ticket of Roosevelt and Hiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917. Johnson achieved national prominence in the early 20th century. He was elected in 191 ...

of California at the 1912 Progressive National Convention. The new party attracted several Republican officeholders, although nearly all of them remained loyal to the Republican Party—in California, Johnson and the Progressives took control of the Republican Party.

The party's platform built on Roosevelt's Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

domestic program and called for several progressive reforms. The platform asserted that "to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day". Proposals on the platform included restrictions on campaign finance

Campaign finance, also known as election finance or political donations, refers to the funds raised to promote candidates, political parties, or policy initiatives and referendums. Political parties, charitable organizations, and political a ...

contributions, a reduction of the tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

and the establishment of a social insurance

Social insurance is a form of social welfare that provides insurance against economic risks. The insurance may be provided publicly or through the subsidizing of private insurance. In contrast to other forms of social assistance, individuals' ...

system, an eight-hour workday

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 1 ...

and women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

. The party was split on the regulation of large corporations, with some party members disappointed that the platform did not contain a stronger call for "trust-busting

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

". Party members also had different outlooks on foreign policy, with pacifists like Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

opposing Roosevelt's call for a naval build-up.

In the 1912 election, Roosevelt won 27.4% of the popular vote compared to Taft's 23.2%, making Roosevelt the only third party presidential nominee to finish with a higher share of the popular vote than a major party's presidential nominee. Both Taft and Roosevelt finished behind Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, who won 41.8% of the popular vote and the vast majority of the electoral vote. The Progressives elected several Congressional and state legislative candidates, but the election was marked primarily by Democratic gains. The 1916 Progressive National Convention was held in conjunction with the 1916 Republican National Convention in hopes of reunifying the parties with Roosevelt as the presidential nominee of both parties. The Progressive Party collapsed after Roosevelt refused the Progressive nomination and insisted his supporters vote for Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, the moderately progressive Republican nominee. Most Progressives joined the Republican Party, but some converted to the Democratic Party and Progressives such as Harold L. Ickes

Harold LeClair Ickes ( ; March 15, 1874 – February 3, 1952) was an American administrator, politician and lawyer. He served as United States Secretary of the Interior for nearly 13 years from 1933 to 1946, the longest tenure of anyone to hold th ...

would play a role in President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's administration. In 1924, La Follette set up another Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

for his presidential run. A third Progressive Party Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ita ...

was set up in 1948 for the presidential campaign of former vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

Henry A. Wallace.

Losing to President Taft

Roosevelt had selected Taft, his

Roosevelt had selected Taft, his Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, to succeed him as the presidential candidate because he thought Taft closely mirrored his own positions. Taft easily won the 1908 presidential election over William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the Democratic Party, running three times as the party's nominee for President ...

. Roosevelt became disappointed by Taft's increasingly conservative policies. Roosevelt was outraged when Taft used the Sherman Anti-Trust Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

Th ...

to sue U.S. Steel for an action that President Roosevelt had explicitly approved. They became openly hostile and Roosevelt decided to seek the presidency in early 1912. Taft was already being challenged by Progressive leader senator Robert La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

of Wisconsin. Most of La Follette's supporters switched to Roosevelt, leaving the Wisconsin senator embittered.

Nine of the states where progressive elements were strongest had set up preference primaries, which Roosevelt won, but Taft had worked far harder than Roosevelt to control the Republican Party's organizational operations and the mechanism for choosing its presidential nominee, the 1912 Republican National Convention. For example, he bought up the votes of delegates from the Southern states, copying the technique Roosevelt himself used in 1904. The Republican National Convention rejected Roosevelt's protests. Roosevelt and his supporters walked out and the convention re-nominated Taft.

The new party

The next day, Roosevelt supporters met to form a new political party of their own. California GovernorHiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917. Johnson achieved national prominence in the early 20th century. He was elected in 191 ...

became its chairman and a new convention was scheduled for August. Most of the funding came from wealthy sponsors. Magazine publisher Frank A. Munsey provided $135,000; and financier George W. Perkins, gave $130,000. Roosevelt's family gave $77,500 and others gave $164,000. The total was nearly $600,000, far less than the major parties.

The leadership of the new party at the level just below Roosevelt included

The leadership of the new party at the level just below Roosevelt included Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

of Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Cha ...

, a leader in social work, feminism, and pacifism; former Senator Albert J. Beveridge

Albert Jeremiah Beveridge (October 6, 1862 – April 27, 1927) was an American historian and US senator from Indiana. He was an intellectual leader of the Progressive Era and a biographer of Chief Justice John Marshall and President Abraham Linco ...

of Indiana, a leading advocate of regulating industry.; Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

, a leading environmentalist. and his brother Amos Pinchot

Amos Richards Eno Pinchot (December 6, 1873 – February 18, 1944) was an American lawyer and reformist. He never held public office but managed to exert considerable influence in reformist circles and did much to keep progressive and Georg ...

, enemy of the trusts. Publishers represented the Muckraker element exposing corruption in city machines. The included Frank Munsey, and Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt durin ...

, who was the Republican Vice-Presidential candidate in 1936. The two main organizers were Senator Joseph M. Dixon

Joseph Moore Dixon (July 31, 1867May 22, 1934) was an American History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican politician from Montana. He served as a U.S. House of Representatives, Representative, United States Senate, Senator, and th ...

of Montana and especially George W. Perkins, a senior partner of the Morgan bank who came from the efficiency movement

The efficiency movement was a major movement in the United States, Britain and other industrial nations in the early 20th century that sought to identify and eliminate waste in all areas of the economy and society, and to develop and implement best ...

. He and Munsey provided financing while Perkins took efficient charge of the new party's organization. However Perkins close ties to Wall Street made him feared and deeply distrusted by many party activists.

The new party had serious structural defects. Since it insisted on running complete tickets against the regular Republican ticket in most states, Republican politicians would have to abandon to support Roosevelt. The exception was California, where the progressive element took control of the Republican Party and Taft was not even on the November ballot. Nationally only five of the 15 most progressive Republican senators joined the new party. Republican legislators, governors, national committeemen, publishers and editors showed comparable reluctance. bolting the old party risked career suicide. Very few Democrats ever joined the new party. However, many independent reformers still signed up. As a result most of Roosevelt's previous political allies supported Taft, including his son-in-law, Congressman Nicholas Longworth

Nicholas Longworth III (November 5, 1869 – April 9, 1931) was an American politician who became Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a Republican. A lawyer by training, he was elected to the Ohio Senate, where he ini ...

of Cincinnati. His wife Alice Roosevelt Longworth

Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth (February 12, 1884 – February 20, 1980) was an American writer and socialite. She was the eldest child of U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt and his only child with his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. L ...

was Roosevelt's most energetic cheerleader. Their public dispute permanently spoiled their marriage.

Progressive convention and platform

Despite these obstacles, the August convention opened with great enthusiasm. Over 2,000 delegates attended, including many women. In 1912, neither Taft nor Wilson endorsed women's suffrage on the national level. The notable suffragist and social workerJane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage ...

gave a seconding speech for Roosevelt's nomination, but Roosevelt insisted on excluding black Republicans from the South (whom he regarded as a corrupt and ineffective element). Yet he alienated white Southern supporters on the eve of the election by publicly dining with black people at a Rhode Island hotel. Roosevelt was nominated by acclamation, with Johnson as his running mate.

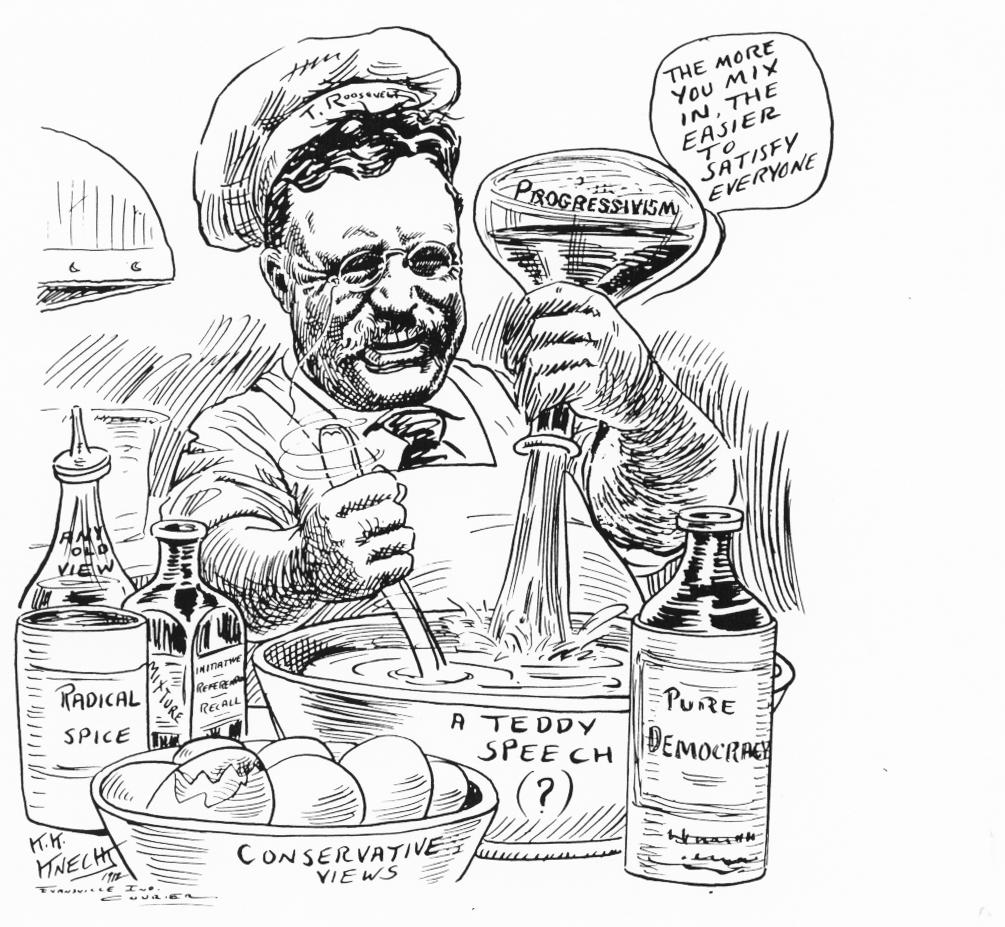

The main work of the convention was the platform, which set forth the new party's appeal to the voters. It included a broad range of social and political reforms long advocated by progressives. It spoke with near-religious fervor and the candidate himself promised: "Our cause is based on the eternal principle of righteousness; and even though we, who now lead may for the time fail, in the end the cause itself shall triumph".

The platform's main theme was reversing the domination of politics by business interests, which allegedly controlled the Republican and Democratic parties, alike. The platform asserted:

To that end, the platform called for:

* Strict limits and disclosure requirements on political

The platform's main theme was reversing the domination of politics by business interests, which allegedly controlled the Republican and Democratic parties, alike. The platform asserted:

To that end, the platform called for:

* Strict limits and disclosure requirements on political campaign contributions

Campaign finance, also known as election finance or political donations, refers to the funds raised to promote candidates, Political party, political parties, or policy initiatives and referendums. Political parties, charitable organizations, a ...

* Registration of lobbyists

* Recording and publication of Congressional committee

A congressional committee is a legislative sub-organization in the United States Congress that handles a specific duty (rather than the general duties of Congress). Committee membership enables members to develop specialized knowledge of the ...

proceedings

In the social sphere, the platform called for:

* A national health service to include all existing government medical agencies

* Social insurance

Social insurance is a form of social welfare that provides insurance against economic risks. The insurance may be provided publicly or through the subsidizing of private insurance. In contrast to other forms of social assistance, individuals' ...

, to provide for the elderly, the unemployed, and the disabled

* Limiting the ability of judges to order injunctions

An injunction is a legal and equitable remedy in the form of a special court order that compels a party to do or refrain from specific acts. ("The court of appeals ... has exclusive jurisdiction to enjoin, set aside, suspend (in whole or in par ...

to limit labor strikes

* A minimum wage law Minimum wage law is the body of law which prohibits employers from hiring employees or workers for less than a given hourly, daily or monthly minimum wage. More than 90% of all countries have some kind of minimum wage legislation.

History

Until r ...

for women

* An eight-hour workday

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses.

An eight-hour work day has its origins in the 1 ...

* A federal securities commission

* Farm relief

* Workers' compensation

Workers' compensation or workers' comp is a form of insurance providing wage replacement and medical benefits to employees injured in the course of employment in exchange for mandatory relinquishment of the employee's right to sue his or her emp ...

for work-related injuries

* An inheritance tax

The political reforms proposed included:

* Women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

* Direct election of senators

* Primary elections for state and federal nominations

Nomination is part of the process of selecting a candidate for either election to a public office, or the bestowing of an honor or award. A collection of nominees narrowed from the full list of candidates is a short list.

Political office

In th ...

* Easier amending of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

The platform also urged states to adopt measures for " direct democracy", including:

* The recall election

A recall election (also called a recall referendum, recall petition or representative recall) is a procedure by which, in certain polities, voters can remove an elected official from office through a referendum before that official's term of of ...

(citizens may remove an elected official before the end of his term)

* The referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

(citizens may decide on a law by popular vote)

* The initiative

In political science, an initiative (also known as a popular initiative or citizens' initiative) is a means by which a petition signed by a certain number of registered voters can force a government to choose either to enact a law or hold a ...

(citizens may propose a law by petition

A petition is a request to do something, most commonly addressed to a government official or public entity. Petitions to a deity are a form of prayer called supplication.

In the colloquial sense, a petition is a document addressed to some offi ...

and enact it by popular vote)

* Judicial recall (when a court declares a law unconstitutional, the citizens may override that ruling by popular vote)

Besides these measures, the platform called for reductions in the tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and pol ...

and limitations on naval armaments by international agreement. The platform also vaguely called for the creation of a national health service, making Roosevelt likely the first major politician to call for health care reform.

The biggest controversy at the convention was over the platform section dealing with trusts and monopolies. The convention approved a strong "trust-busting" plank, but Perkins had it replaced with language that spoke only of "strong National regulation" and "permanent active ederalsupervision" of major corporations. This retreat shocked reformers like Pinchot, who blamed it on Perkins. The result was a deep split in the new party that was never resolved.

The platform in general expressed Roosevelt's " New Nationalism", an extension of his earlier philosophy of the Square Deal

The Square Deal was Theodore Roosevelt's domestic program, which reflected his three major goals: conservation of natural resources, control of corporations, and consumer protection.

These three demands are often referred to as the "three Cs" ...

. He called for new restraints on the power of federal and state judges along with a strong executive to regulate industry, protect the working classes and carry on great national projects. This New Nationalism was paternalistic, in direct contrast to Wilson's individualistic philosophy of " New Freedom". However, once elected, Wilson's actual program resembled Roosevelt's ideas, apart from the notion of reining in judges.

Roosevelt also favored a vigorous foreign policy, including strong military power. Though the platform called for limiting naval armaments, it also recommended the construction of two new battleships per year, much to the distress of outright pacifists such as Jane Addams.

Elections

1912

Roosevelt ran a vigorous campaign, but the campaign was short of money as the business interests which had supported Roosevelt in 1904 either backed the other candidates or stayed neutral. Roosevelt was also handicapped because he had already served nearly two full terms as president and thus was challenging the unwritten "no third term" rule.

In the end, Roosevelt fell far short of winning. He drew 4.1 million votes—27%, well behind Wilson's 42%, but ahead of Taft's 23% (6% went to

Roosevelt ran a vigorous campaign, but the campaign was short of money as the business interests which had supported Roosevelt in 1904 either backed the other candidates or stayed neutral. Roosevelt was also handicapped because he had already served nearly two full terms as president and thus was challenging the unwritten "no third term" rule.

In the end, Roosevelt fell far short of winning. He drew 4.1 million votes—27%, well behind Wilson's 42%, but ahead of Taft's 23% (6% went to Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

Eugene Debs

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the sin ...

). Roosevelt received 88 electoral votes, compared to 435 for Wilson and 8 for Taft. This was nonetheless the best showing by any third party since the modern two-party system was established in 1864. Roosevelt was the only third-party candidate to outpoll a candidate of an established party.

U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

(the exact number is not clear because there were many Republican-Progressive fusion candidacies and some candidates ran with the labels of ''ad hoc'' groups such as "Bull Moose Republicans" or (in Pennsylvania) the "Washington Party".)

On October 14, 1912, while Roosevelt was campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, an insane man John Flammang Schrank

On October 14, 1912, former saloonkeeper John Flammang Schrank (1876–1943) attempted to assassinate former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt while he was campaigning for the presidency in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Schrank's bullet lodged in Roos ...

, shot him, but the bullet lodged in his chest only after penetrating both his steel eyeglass case and a 50-page single-folded copy of the speech titled "''Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual

Progressive may refer to:

Politics

* Progressivism, a political philosophy in support of social reform

** Progressivism in the United States, the political philosophy in the American context

* Progressive realism, an American foreign policy par ...

''", he was to deliver, carried in his jacket pocket. Schrank was immediately disarmed, captured and might have been lynched had Roosevelt not shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed. Roosevelt assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and to make sure no violence was done to him. As an experienced hunter and anatomist, Roosevelt correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung and he declined suggestions to go to the hospital immediately. Instead, he delivered his scheduled speech with blood seeping into his shirt. He spoke for 90 minutes before completing his speech and accepting medical attention. His opening comments to the gathered crowd were: "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose". Afterwards, probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle, but did not penetrate the pleura

The pulmonary pleurae (''sing.'' pleura) are the two opposing layers of serous membrane overlying the lungs and the inside of the surrounding chest walls.

The inner pleura, called the visceral pleura, covers the surface of each lung and dips b ...

. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life. In later years, when asked about the bullet inside him, Roosevelt would say: "I do not mind it any more than if it were in my waistcoat pocket".

Both Taft and Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson suspended their own campaigning until Roosevelt recovered and resumed his. When asked if the shooting would affect his election campaign, he said to the reporter "I'm fit as a bull moose", which inspired the party's emblem. He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail. Despite his tenacity, Roosevelt ultimately lost his bid for reelection.State and local operations

=Ohio

= Ohio provided the greatest level of state activity for the new party, as well as the earliest formations. In November 1911, a group of Ohio Republicans endorsed Roosevelt for the party's nomination for president; the endorsers included James R. Garfield and Dan Hanna. This endorsement was made by leaders of President Taft's home state. Roosevelt conspicuously declined to make a statement—requested by Garfield—that he would flatly refuse a nomination. Soon thereafter, Roosevelt said, "I am really sorry for Taft... I am sure he means well, but he means well feebly, and he does not know how! He is utterly unfit for leadership and this is a time when we need leadership." In January 1912, Roosevelt declared "if the people make a draft on me I shall not decline to serve". Later that year, Roosevelt spoke before the Constitutional Convention in Ohio, openly identifying as a progressive and endorsing progressive reforms—even endorsing popular review of state judicial decisions. In reaction to Roosevelt's proposals for popular overrule of court decisions, Taft said, "Such extremists are not progressives—they are political emotionalists or neurotics". The showdown came in Ohio's primary on May 21, 1912, in Taft's home state. Both the Taft and Roosevelt campaigns worked furiously, and La Follette joined in. Each team sent in big name speakers. Roosevelt's train went 1800 miles back and forth in the one state, where he made 75 speeches. Taft's train went 3000 miles criss-crossing Ohio and he made over 100 speeches. Roosevelt swept the state, convincing Roosevelt that he should intensify his campaigning, and letting Taft know he should work from the White House not the stump.=November 1912

= Most of the Progressive candidates were in New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Massachusetts. Very few were in the South. In one major state California, the state Republican Party was controlled by Governor Hiram Johnson, a close ally of Roosevelt, He became the vice presidential nominee and the ticket carried California. Only a third of the states held primaries; elsewhere the state organization chose the delegations to the national convention and they favored Taft. The final credentials of the state delegates at the national convention were determined by the national committee, which was controlled by Taft men. The Progressive candidates generally got between 10% and 30% of the vote. Nine Progressives were elected to the House and none won governorships. About 250 Progressives were elected to local offices. In November the Democrats benefitted from the Republican split--very few Democrats voted for the Progressive candidates. They gained many state legislature seats, which gave them 10 additional U.S. Senate seats—they also gained 63 U.S. House seats.1914

Despite the second-place finish of 1912, the Progressive Party did not disappear at once. One hundred thirty-eight candidates, including women, ran for the U.S. House as Progressives in 1914 and 5 were elected. However, almost half the candidates failed to get more than 10% of the vote.Gifford Pinchot

Gifford Pinchot (August 11, 1865October 4, 1946) was an American forester and politician. He served as the fourth chief of the U.S. Division of Forestry, as the first head of the United States Forest Service, and as the 28th governor of Pennsy ...

placed second in the Senate election in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, gathering 24% of the vote.

Hiram Johnson was denied renomination for governor as a Republican—he ran as a Progressive and was re-elected. Seven other Progressives ran for governor; none got more than 16%. Some state parties remained fairly strong. In Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Progressives won a third of the seats in the Washington State Legislature.

1916

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

businessman John M. Parker ran for governor as a Progressive early in the year as the Republican Party was deeply unpopular in Louisiana. Parker got a respectable 37% of the vote and was the only Progressive to run for governor that year.

Later that year, the party held its second national convention, in conjunction with the Republican National Convention as this was to facilitate a possible reconciliation. Five delegates from each convention met to negotiate and the Progressives wanted reunification with Roosevelt as nominee, which the Republicans adamantly opposed. Meanwhile, Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, a moderate Progressive, became the front-runner at the Republican convention. He had been on the Supreme Court in 1912 and thus was completely neutral on the bitter debates that year. The Progressives suggested Hughes as a compromise candidate, then Roosevelt sent a message proposing conservative senator Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

. The shocked Progressives immediately nominated Roosevelt again, with Parker as the vice presidential nominee. Roosevelt refused to accept the nomination and endorsed Hughes, who was immediately approved by the Republican convention.Fred L. Israel, "Bainbridge Colby and the Progressive Party, 1914–1916". ''New York History'' 40.1 (1959): 33–46. .

The remnants of the national Progressive party promptly disintegrated. Most Progressives reverted to the Republican Party, including Roosevelt, who stumped for Hughes; and Hiram Johnson, who was elected to the Senate as a Republican. Some leaders, such as Harold Ickes of Chicago, supported Wilson.

1918

All the remaining Progressives in Congress rejoined the Republican Party, except Whitmell Martin, who became a Democrat. No candidates ran as Progressives for governor, senator or representative.Later years

Robert M. La Follette Sr.

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

broke bitterly with Roosevelt in 1912 and ran for president on his own ticket, the 1924 Progressive Party, during the 1924 presidential election.

From 1916 to 1932, the Taft wing controlled the Republican Party and refused to nominate any prominent 1912 Progressives to the Republican national ticket. Finally, Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt durin ...

was nominated for vice president in 1936.

The relative domination of the Republican Party by conservatives left many former Progressives with no real affiliation until the 1930s, when most joined the New Deal Democratic Party coalition of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.

Electoral history

In congressional elections

In presidential elections

Office holders from the Progressive Party

See also

* Committee of 48 *Lincoln–Roosevelt League The Lincoln–Roosevelt League (officially known as the League of Lincoln-Roosevelt Republican Clubs) was founded in 1907 by California journalists Chester H. Rowell of the ''Fresno Morning Republican'' and Edward Dickson of the ''Los Angeles Expre ...

, the California Progressive Party in the early 1900s

* Populist Party (United States)

* Progressive Party (United States, 1924) Progressive Party may refer to:

Active parties

* Progressive Party, Brazil

* Progressive Party (Chile)

* Progressive Party of Working People, Cyprus

* Dominica Progressive Party

* Progressive Party (Iceland)

* Progressive Party (Sardinia), Ital ...

* Progressive Party (United States, 1948)

* California Progressive Party

The California Progressive Party, also named California Bull Moose, was a political party that flourished from 1912 to 1944 and lasted through the 1960s.

In 1910, Hiram W. Johnson, a nominal Republican who was backed by suffragette and early femi ...

* Oregon Progressive Party

The Oregon Progressive Party is a political party in the U.S. state of Oregon. Originally called the Oregon Peace Party, it was accepted as the sixth minor statewide political party in Oregon on August 22, 2008. This allowed the party to nomi ...

* Wisconsin Progressive Party

The Wisconsin Progressive Party (1934–1946) was a political party that briefly held a dominant role in Wisconsin politics. History

The Party was the brainchild of Philip La Follette and Robert M. La Follette, Jr., the sons of the famous Wisco ...

* Minnesota Progressive Party

The United States Progressive Party of 1948 was a left-wing political party in the United States that served as a vehicle for the campaign of Henry A. Wallace, a former vice president, to become President of the United States in 1948. The party ...

* Vermont Progressive Party

The Vermont Progressive Party, formerly the Progressive Coalition, is a progressive political party in the United States founded in 1999 and active only in the state of Vermont. As of 2019, the party has two members in the Vermont Senate and se ...

Footnotes

Further reading

* Broderick, Francis L. ''Progressivism at risk: Electing a President in 1912'' (Praeger, 1989). * Chace, James. ''1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft & Debs—the Election That Changed the Country'' (2004). * Cole, Marena. "A Progressive Conservative": The Roles of George Perkins and Frank Munsey in the Progressive Party Campaign of 1912" (Thesis , Tufts University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2017. 10273522). * Cowan, Geoffrey. ''Let the People Rule: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary'' (2016). * Delahaye, Claire. "The New Nationalism and Progressive Issues: The Break with Taft and the 1912 Campaign," in Serge Ricard, ed., ''A Companion to Theodore Roosevelt'' (2011) pp. 452–467online

* Flehinger, Brett. ''The 1912 Election and the Power of Progressivism: A Brief History with Documents'' (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2003). * Gable, John A. ''The Bullmoose Years: Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Party''. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1978. * Garraty, John A. ''Right Hand Man: The Life of George W. Perkins'', (1960

online

* Goodwin, Doris Kearns. ''The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism'' (2013) * Gould, Lewis L. ''Four hats in the ring: The 1912 election and the birth of modern American politics'' (University Press of Kansas, 2008). * Jensen, Richard. "Theodore Roosevelt" in ''Encyclopedia of Third Parties'' (ME Sharpe, 2000). pp. 702–707. * Karlin, Jules A. ''Joseph M. Dixon of Montana'' (U of Montana Publications in History, 1974) 1:130-190. * Kraig, Robert Alexander. "The 1912 Election and the Rhetorical Foundations of the Liberal State". ''Rhetoric and Public Affairs'' (2000): 363–395. . * Lincoln, A. “Theodore Roosevelt, Hiram Johnson, and the Vice-Presidential Nomination of 1912.” ''Pacific Historical Review'' 29#3 (1959), pp. 267–83

online

* Milkis, Sidney M., and Daniel J. Tichenor. "Direct Democracy' and Social Justice: The Progressive Party Campaign of 1912". ''Studies in American Political Development'' 8#2 (1994): 282–340. * Milkis, Sidney M. ''Theodore Roosevelt, the Progressive Party, and the Transformation of American Democracy''. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009. * Mowry, George E. ''The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America''. New York: Harper and Row, 1962, national survey; it is not biographical on Roosevel

online

* Mowry, George E. ''Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement''. (1946) focus on 1912

online

* Ness, Immanuel, and James Ciment, eds. ''The Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America'' (3 vol. 2000). * Selmi, Patrick. "Jane Addams and the Progressive Party Campaign for President in 1912". ''Journal of Progressive Human Services'' 22.2 (2011): 160–190.

State and local studies

* Buenker, John D. ''Urban Liberalism and Progressive Reform'' (1973). * Buenker, John D. ''The History of Wisconsin, Vol. 4: The Progressive Era, 1893–1914'' (1998). * Deverell, William, and Tom Sitton, eds. ''California Progressivism Revisited'' ( Univ of California Press, 1994)online

* Huthmacher, J. Joseph. "Urban Liberalism and the Age of Reform" ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' 49 (1962): 231–241, ; emphasized urban, ethnic, working class support for reform * Link, William A. ''The Paradox of Southern Progressivism, 1880–1930'' (1992). * Maxwell, Robert S. ''La Follette and the Rise of the Progressives in Wisconsin''. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1956. * Mowry, George E. ''The California Progressives'' (U of California Press, 1951)

online

* Olin, Spencer C. ''California's Prodigal Sons'' (Univ of California Press, 1968

online

* Pegram, Thomas R. ''Partisans and Progressives: Private Interest and Public Policy in Illinois, 1870-1922'' (U of Illinois Press, 1992)

online

* Recchiuti, John Louis. ''Civic Engagement: Social Science and Progressive-Era Reform in New York City'' (2007). * Warner, Hoyt Landon. ''Progressivism in Ohio 1897-1917'' (Ohio State UP, 1964) * Wesser, Robert F. ''Charles Evans Hughes: politics and reform in New York, 1905–1910'' (1967). * Wright, James. ''The Progressive Yankees: Republican Reformers in New Hampshire, 1906-1916'' (1987).

Primary sources

* "Progressive Party Platform of 1912online

* DeWitt, Benjamin P. ''The Progressive Movement: A Non-Partisan, Comprehensive Discussion of Current Tendencies in American Politics'' (1915)

online

* Pinchot, Amos. ''What's the Matter with America: The Meaning of the Progressive Movement and the Rise of the New Party''. (1912

online

* Pinchot, Amos. ''History of the Progressive Party, 1912–1916''. Introduction by Helene Maxwell Hooker. (New York University Press, 1958

online

* Roosevelt, Theodore. ''Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt'' Ed. Lewis L. Gould. (UP of Kansas, 2008).

External links

TeddyRoosevelt.com: Bull Moose Information

Theodore Roosevelt Speech Edison Recordings Campaign - 1912

''1912 Progressive Party platform''

at

LibriVox

LibriVox is a group of worldwide volunteers who read and record public domain texts, creating free public domain audiobooks for download from their website and other digital library hosting sites on the internet. It was founded in 2005 by Hugh Mc ...

(public domain audiobooks)

{{Authority control

Progressive Era in the United States

Left-wing populism in the United States

Political parties in the United States